DAY IN THE LIFE OF DANCE: Graham in the Studio with Hope Boykin, Developing "En Masse"

Catch "En Masse" at the Martha Graham Dance Company’s 100th Anniversary Season at NY City Center, April 9-12, 2026

Choreographer: Hope Boykin

Musicians: Leonard Bernstein and Christopher Rountree

Assistants to the choreographer: Cameron Harris and Terri Ayanna Wright

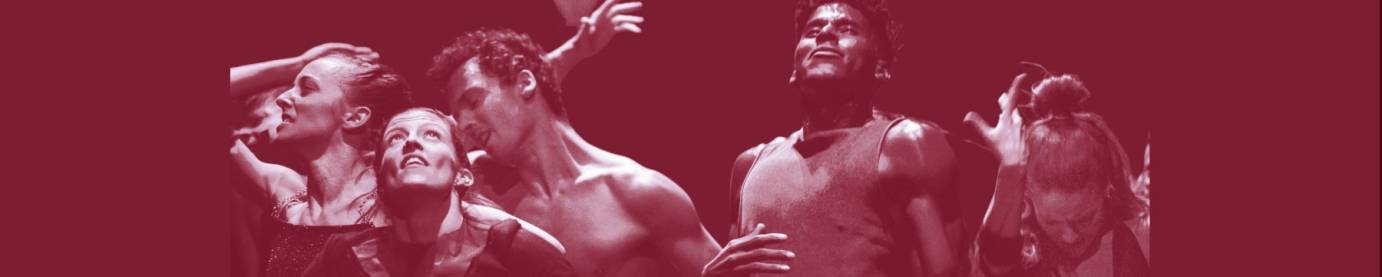

Dancers: Zachary Jeppsen-Toy, Meagan King, Lloyd Knight, Jai Perez, Anne Souder, Leslie Andrea Williams, Xin Ying

Two weeks before her new piece, En Masse, received its premiere at The Soraya Center for the Performing Arts on October 4, 2025 in Northridge, California, choreographer Hope Boykin welcomed supporters to an open rehearsal at the Martha Graham Studio Theater in Manhattan’s Westbeth. With the finish-line in sight, Boykin was racing to complete this high-profile commission, set to a suite from Leonard Bernstein’s Mass, for the Martha Graham Dance Company's 100th-anniversary season.

“I don’t count the days, I count the minutes — including breaks,” she said. Yet the choreographer looked cheerful, appearing to relish the challenge.

The rehearsal, on September 24, offered tantalizing glimpses of the work-in-progress, along with commentary by Boykin and her musical collaborator, Christopher Rountree. Janet Eilber, the Graham company’s stalwart artistic director, opened the conversation. According to Eilber, this commission began to take shape during a discussion with Rountree, a disruptor on the L.A. music scene, who has worked with the Graham company in the past. Rountree recalled that when he first heard Bernstein’s Mass, in his youth, the piece influenced his decision to become a conductor; and Eilber recalled that the late choreographer Martha Graham, who championed the work of American composers, had explored the possibility of collaborating with Bernstein in the 1980s. A search of Bernstein’s archives at the Library of Congress then unearthed a musical sketch, only 49 seconds long but still viable, which Bernstein had composed with Graham in mind.

Bernstein’s Mass created a political furor when it received its premiere, in 1971, at the opening of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, in our nation’s capital. In the midst of the Vietnam War, the production demanded an immediate end to hostilities, and it included disaffected characters who questioned their religious faith. The work represented “a moment of true activism,” Rountree says. Using the Latin mass as the framework for an outsize, theatrical spectacle, Mass incorporated a diversity of musical styles, including rock ‘n roll and jazz. The original production also featured choreography by the late Alvin Ailey, which is how Boykin became involved in this new venture.

An esteemed veteran of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Boykin felt a connection with the work through her mentor, Judith Jamison, who had danced in the original production; and Boykin had her own shot at choreographing Mass, when the Kennedy Center celebrated the production’s 50th anniversary in 2022.

Boykin’s new piece, En Masse, is not a full-scale revival of Bernstein’s Mass, however, but a suite extracted from it, with additional music by Rountree and variations on the theme in that sketch discovered at the Library of Congress. Refitting the music to a new purpose forced the creative team to make difficult decisions. Initially, they had to decide whether to use Mass’s lyrics, or to present the work as an abstract composition emphasizing rhythm. (They chose to keep the words.) As Boykin worked, her choreography began to make its own needs felt.

“Do we extend a fermata at the end of a phrase?” Rountree asked, citing a relatively minor accommodation.

“This was probably one of [my] hardest commissions,” Boykin commented. “I was so tied to it,” she said, “I had to honor the music as well as make steps.”

At this writing, the new dance remained incomplete, and the preview in the studio was a working rehearsal. Passing over holes in the composition with a shrug and a grin (she would get to that part later), Boykin focused on shaping the movement to her liking. Her body swayed as she demonstrated an impulse that rose from the hips and traveled through the ribcage. At another point, as the ensemble advanced from the corner in a wedge, stamping their feet and punching the air, Boykin told them, “I don’t think you should melt, I think you should dig.” In contrast to sections with clearly defined architecture, others showed the dancers jogging or drifting individually through the space, passing through lines the way a ghost might pass through a wall.

As an Ailey dancer, Boykin knows what to do with a soloist, and clearly she intends to exploit the Graham company’s star power. In one segment, Lloyd Knight advanced at a tilt, gesturing with an open palm and beginning a gentle, lyrical solo that emphasized his long arms and sculpted torso. Boykin encouraged him to luxuriate in the movement. “Your time is your time,” she told him. At another point, dramatic Xin Ying appeared shrinking and cowed, her arms loosely unfolding. Overthrown, she fell to the floor, panting and grieving. “Fade! Fade! Fade!” Boykin called out, marking a future lighting cue. Feisty Meagan King often separated from the group. Sometimes she was lifted in an apparent rescue, while other times she stood apart, tense and isolated.

Boykin and the dancers were still learning how to handle a prop — blue rubber bands that tied the performers’ wrists. Do these bands represent shackles, or bind together a community?

“That’s your drama, your baggage,” Boykin explained in answer to an audience member’s question. A program note explained that En Masse suggests the progress we can make when we work together, but the dance’s meaning, like the choreography, was still unfolding. “Just make the steps, and the context will come,” Boykin said.