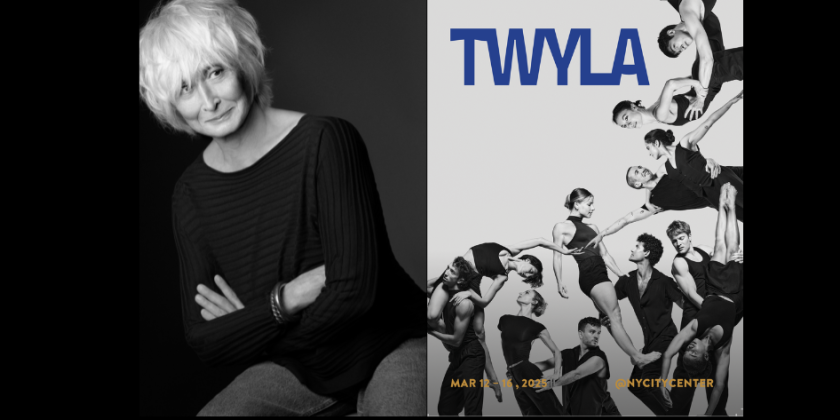

IMPRESSIONS: American Ballet Theatre in “Twyla@60: A Tharp Celebration”

Choreography: Twyla Tharp

Music: Colin Jacobsen, Café Tacvba, Ljova, J.S. Bach, Joseph Lamb, Haydn

Costumes: Santo Loquasto

Lighting: David Finn (recreated by Brad Fields), Jennifer Tipton

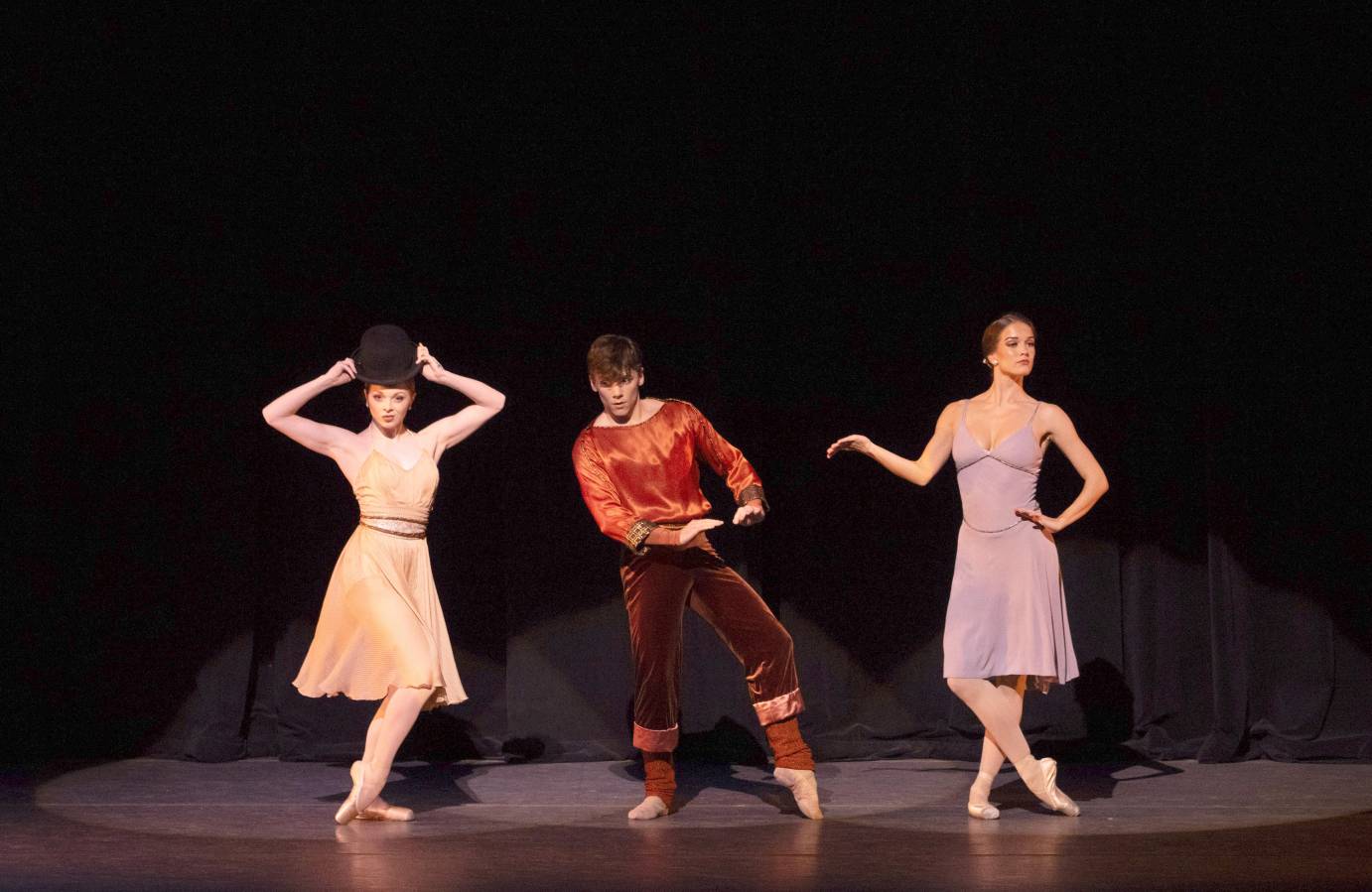

Featured Dancers: Isaac Hernández, Catherine Hurlin, Chloe Misseldine, James Whiteside, Jarod Curley, Carlos Gonzalez, Sunmi Park, Jake Roxander, Madison Brown, Zimmi Coker, Kanon Kimura, Cy Doherty, Tyler Maloney, Andrew Robare, Yoon Jung Seo, Olivia Tweedy

David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, New York, NY

October 15, 16, 18 and 24, 2025

I caught the last performance of Twyla@60: A Tharp Celebration — one of four programs making up American Ballet Theatre’s fall season at Lincoln Center. Sadly, it wasn’t as entertaining as I’d expected, though the dancing was nothing short of spectacular!

A mini-retrospective of sorts, honoring the pioneering postmodern choreographer Twyla Tharp’s long history of creating works for ABT, the triple bill comprises her first work for the company, the comic Push Comes to Shove, created in 1976 for Mikhail Baryshnikov; Bach Partita, a neo-classical ballet Tharp choreographed for the troupe in 1983; and Sextet, a piece full of challenging partner-work for three couples. Though originally made on four dancers from ABT (including the troupe’s current artistic director, Susan Jaffe) and two members of New York City Ballet, Sextet was presented publicly for the first time in 1992, by Twyla Tharp Dance, and here received its ABT company premiere.

Because of its title, I anticipated a program commemorating Tharp’s 60 years as a choreographer. It was in 1965, after performing for two years with the Paul Taylor Dance Company, that Tharp presented the first concert of her own choreography. Yet the evening’s fare is not marked by the signature irreverence nor the imaginatively pedestrian, boundary-pushing, jazz-inflected, loosey-goosey, athletic movement style for which Tharp is known. It doesn’t deliver the kind of radically avant-garde or popular music-influenced choreography Tharp created for other companies and for stage and movie musicals. You won’t see the likes of Deuce Coupe (1973), her break-out ballet set to Beach Boys tunes, or even Nine Sinatra Songs (1982), much less anything like her chorography for Broadway’s Movin’ Out (2002) or Hollywood’s Hair (1979).

The program focuses only on Tharp choreography made specifically for classical dancers. Wisely, rather than imposing on them her inventive modern vocabulary — which so ensnared audiences in other arenas — for ABT’s world-class ballet dancers Tharp devised works that would display as well as extend what it is they already do so well.

During my dancing days, decades ago, I auditioned for a Tharp performance project and found the movement phrases virtually impossible for my ballet-trained body to master (I didn’t even make the first cut). What I found so difficult was the melding of pulled-up technical feats with a contrasting weighty casualness, all sparked by unexpected accents, directional changes, and rhythmic syncopation. Yet that’s what makes Tharp’s choreography so captivating to watch!

Her works for ballet dancers, however, don’t do that kind of blending of opposing movement qualities, at least not within a single dancing body. Rather they combine a step of this with a bit of that, sometimes performed simultaneously by a dancer and her partner, or in a rapid sequence of discrete movements. For example, in Sextet — fueled by sensuous, percussion-heavy music by Colin Jacobsen, Café Tacvba, and Ljova, that sounds, at times, Latin-American, tango-esque, or folksily Eastern European — a classical arabesque is preceded by a pop-dance step-touch move, while a flexed-foot dig launches a series of chainé turns on pointe. Dazzling strings of multiple pirouettes are framed by a partner walking with Latin ballroom hip motion. Flamenco and folk-dance borrowings are also inserted into the mix, yet the classical lines remain clear as the mixture lies not baked within individual movements, but rather in how they are all arranged. On only one occasion, when an entrechat jump is performed with a downward focus and hunched shoulders, does it feel as though ballet vocabulary is being infused with something suggesting a new movement language on the horizon.

However, in its whiplash switches from ballet to pedestrian or social-dance vocabulary, and the use of the music’s prestissimo passages and ethnic flavors to push the dancers’ speed and stylistic range, we start to see how Tharp’s choreography significantly expanded ballet dancers’ performance capabilities. And that becomes even more visible in the virtually non-stop motion of the evening’s centerpiece, Bach Partita. It’s composed of tricky phrases, densely packed with quick transferences of weight, off-centered alignment, backward movements (a direction not commonly explored in classical choreography) and not much in the way of posing — that holding of still shapes for admiration that ballet dancers are so beautifully trained to do. But from a technical standpoint, it’s pure ballet — that is, ballet of George Balanchine’s neo-classical variety.

Even the least discerning balletomane will recognize the Balanchinean influences at work in Tharp’s Bach Partita. And not just in its sleek neo-classical vocabulary. Despite its stage-full of speedily moving dancers, the ballet is accompanied by a solo violin, which lends a tightly focused air to the proceedings and really trains our eye on the particulars of what we’re seeing. We sense a Balanchine-like musicality in Tharp’s mining of the Bach score for all its intricate rhythms, melodic arcs, and exciting accelerations. Moreover, while we usually appreciate Tharp’s choreography for its startling use of the dancing body, in this work — involving three principal couples, featured soloists, and a female corps de ballet — we see Tharp brilliantly exploring the spatial elements of stage composition and geometric designs in a decidedly Balanchinean manner.

With its vaudevillian sensibilities and parodic humor, the program closer, Push Comes to Shove, registers as the most “Tharpian” piece on the bill. Disappointingly, in the lead role of the mischievous master-of-ceremonies trying to inject fun into the takes-itself-too-seriously art of ballet, Jake Roxander performed with magnificent physical prowess but nowhere near enough sly playfulness. Roxander’s technique is astounding, and don’t get me wrong, I am happy to watch him dance any role, anytime, anywhere. But here, where Baryshnikov’s stamp on the part is so indelible, I wanted to be led into the ballet’s raucous goings-on by a more enticingly-drawn character. Roxander appealingly displayed that ability to toss off astonishing tricks then quickly assume a casual, “oh that was nothing” posture — an “attitude” originally perfected by Baryshnikov and now much imitated by virtuoso male dancers seeking to enchant. But in his efforts to balance his character’s rowdy energies with a “cool guy” persona, Roxander leaned too much into the “coolness,” and instead of “winking” at us while his antics shook up the ballet world, he seemed, at times, jaded.

Set to a score that juxtaposes a Haydn symphony and ragtime music by Joseph Lamb, underlining the work’s “jazz up the ballet” concept, the choreography delightfully spoofs Romantic and classical ballet traditions, as well as those psychological, Tudor-esque “modern ballets” of the 20th century. And whatever fun may be missing from Roxander’s interpretation of his character is made up for by Olivia Tweedy and Zimmi Coker. Though initially reluctant, their characters become game supporters of the efforts to disrupt, and wind up finding great glee leading an ensemble that spices ballet phrases with shimmies, hip swings, circling wrists, and ragdoll-like flop overs.

The ballet grows increasingly funnier as it progresses, because the comedy in the later scenes relies less on Roxander’s solo performance and more on the ensemble choreography. Having “loosened things up” to a near-chaotic degree, Roxander darts hilariously amid the dancers trying to avoid collisions while insistently placing his bowler hat atop the heads of different dancing women. In a final determination to make his mark — or should we say Tharp’s mark — he exits the stage and, from the wings, throws one hat after another at the dancers, a last-ditch attempt to make these bunheads perform in a new “fashion.”