MOVING VISIONS: Why Are Freelance Dancers So Upbeat These Days?

Meet Freelance Dancers Deniz Erkan Sancak, Emily Pope, and Leslie Cuyjet

Freelance dancers in New York are like any chorus line on Broadway: They don’t get credit and yet they hold down the fort. The reason the musical A Chorus Line is so popular is that it gives visibility to dancers who work hard but are nearly invisible. In the case of independent dancers in our urban environment, however, they can be very visible.

In order to get work as a freelancer, you have to have a vivid stage presence ontage, be technically strong, and be willing to try anything. By sacrificing a regular paycheck, they get the freedom to choose whom they work with. In doing so, they contribute a wide palette of qualities and cultures to our dance scene. The fact that New York City is chock-full of freelancers of all ages, genres, and races is something to celebrate. Even though big chunks of funding have been grabbed back by our reckless federal regime, freelancers don’t feel the crunch. They don’t have to raise money for the productions they rehearse for — and they are used to a life of risk. I’m going to introduce you to three such dancers: Deniz Erkan Sancak, Emily Pope, and Leslie Cuyjet.

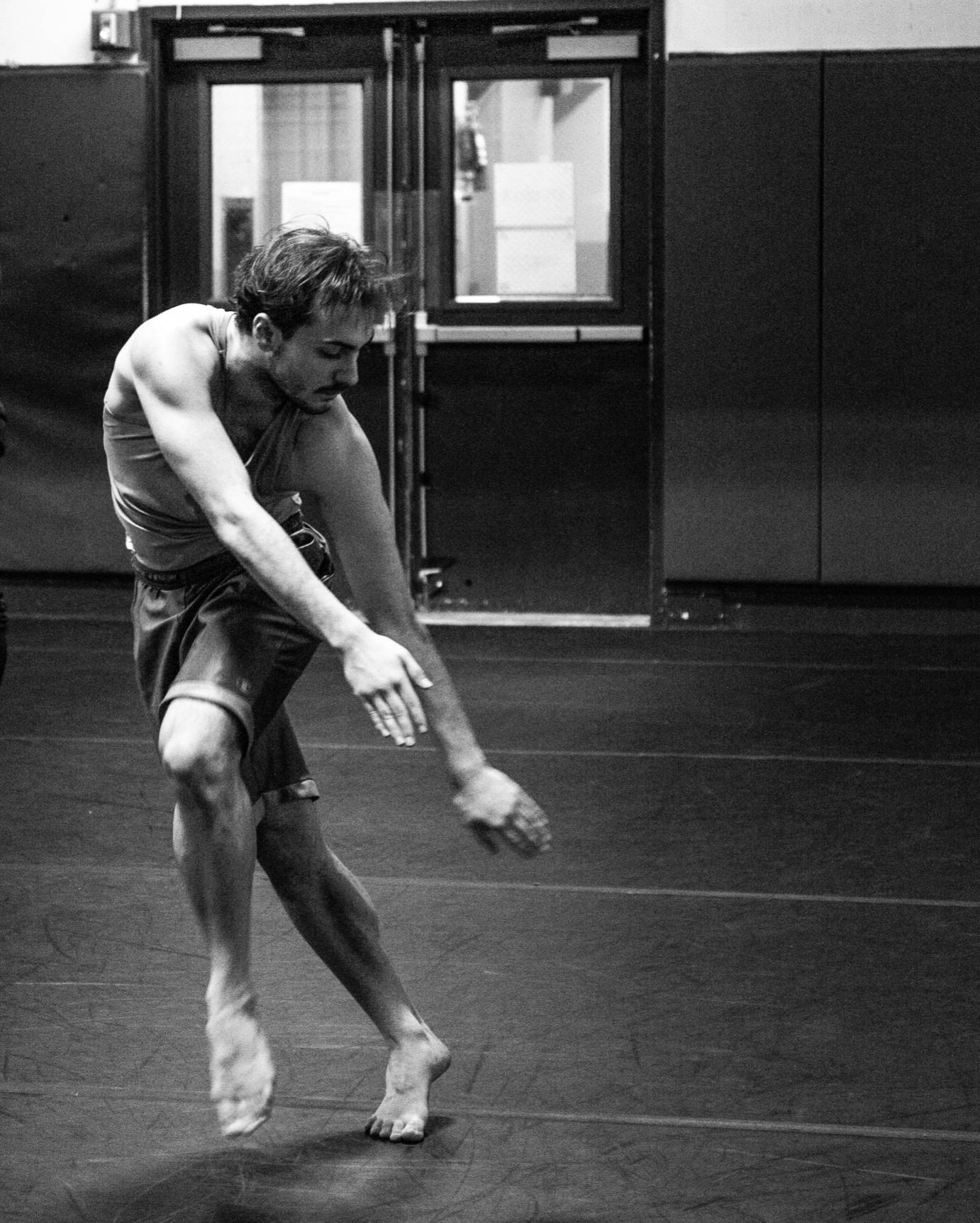

Deniz Sancak has fierce ballet legs and an expressive modern dance torso. Within minutes of watching him, it’s easy to see why critic Brendan McCall called his dancing “gorgeous.” In his review in thINKingdance.net about a showing of Stephen Petronio’s company, McCall goes on to say, “I watch his long limbs move at the speed of controlled chaos, and his spine ripples in complex fractal patterns.”

Deniz is ideal for Petronio’s work. Shortly after he joined the company, however, the choreographer announced his farewell. Luckily, Deniz had already been dancing with other choreographers. But he really wanted to dive into more roles of Petronio’s serpentine and sexy choreography.

Deniz grew up in Ankara, where he was a member of the Turkish National Latin-Ballroom Dance team. He also performed contemporary works and won a scholarship to come to the U.S. to attend SUNY Purchase Conservatory of Dance. After graduating in 2022, he quickly rose to become a sought-after dancer. From small performance spaces like Roulette in Brooklyn, where he performed with Yoshiko Chuma and the School of Hard Knocks, to the grandest theater in the country — the Metropolitan Opera House — he fits in everywhere.

In addition to those two extremes, Deniz has also been working with Douglas Dunn, Christopher Williams, Liz Gerring, and Ellen Cornfield. Schedules can be difficult. Sometimes he would rehearse for three or more choreographers in a day. “During these times,” he said, “these words are circling around my body and mind: ‘Frustrating, refreshing and rewarding.’ ”

The expectations of each gig are completely different. Last fall, for the Metropolitan Opera production of Ainadamar, choreographer Deborah Colker asked Deniz to understudy the main flamenco solo, and she also made a new dance specifically for him. For Douglas Dunn’s work, the movement may fall loosely in the Merce Cunningham vein spiked with poetic idiosyncrasies. With Yoshiko Chuma, he often improvises according to a loosely scripted score — along with improvising musicians.

Although he rises to each different occasion with his usual brilliance, there is one constant: “I am representing myself wherever I go. I am my culture, my ethnics, my history, my intelligence and many more subjects that I have in me. So I contribute ‘me’ to whatever I can be a part of here.”

A freelance life can be fulfilling but demanding. Deniz puts it this way: “You grow so much, you see so much, and you do that fast, because otherwise you don’t exist.”

Emily Pope is an expansive dancer with clean lines, a sharp attack, and an open-faced, gleaming look. She brings a light with her. She’s versatile enough onstage to deliver a poignant spoken story, as she did in Hilary Easton’s Ringelblum at Gibney last month. While she’s in demand as a dancer now, in the past she’s taken odd jobs to keep herself afloat. She’s worked as a waitress, bartender, cafe manager/barista, camp counselor, yoga instructor, and model for live drawing class. She was invited to join a top dance company but turned it down because the aesthetic didn’t suit her.

She knows herself and wants to be able to choose each project. But her daily life can be harried: “I run around a lot, trying to catch trains. It requires a different type of mental focus to switch gears from one environment to another. I have to multitask sometimes on the train, write an email, stretch, do some meditation or Reiki, eat my snack, rehydrate, check off my to-do list in order to reset or prepare for what is next.”

But she relishes dancing a wide variety of roles, from a doctor who succumbs to an erotic encounter with a faun (courtesy of Tamar Rogoff) to a source of peace and comfort in Megan Williams’ Visible last June, to a technical powerhouse for Douglas Dunn. She has also danced with Tiffany Mills, Yoshiko Chuma and the School of Hard Knocks, Bodymouth Productions, Laura Peterson, and Hannah Barnard — just in the last year!

Since she’s been doing this project-hopping for two decades, I asked Emily what changes she has seen. Coming out of the pandemic, she said, “The dance community has actually pulled together in some bigger sense. There’s more of a burning desire to have art be the cathartic revolution. People are using art as a way to build community, heal community, and activate spaces politically.”

Looking back even further, she feels that choreographers are more tolerant of dancers who are mothers. About twenty years ago, it was rare that a freelance dancer could show up to rehearsal with kid in tow. But, she says, “I got lucky. Almost everyone I worked for was also a parent. And I got to take Savannah with me on tour.” Her advice for dancers who have a child: “Work with people who know you’re a parent or at least trust you enough to see you as a person with a life outside of the studio.”

Like Deniz and Emily, Leslie Cuyjet is someone people want to work with. She’s a luscious mover who’s not afraid to be awkward. She’s danced with Jane Comfort, Cynthia Oliver, Juliana May, and an array of others. What she looks for in collaborators are “people I want to be in rooms with to cultivate an exciting, creative environment.”

Because she was so busy, staying fully present in the studio was a challenge for Leslie. About 10 years ago she was pulled in so many directions that a choreographer who was a friend had to tell her, “You're on time, you're here, but I never feel you fully present.” Leslie realized she was doing too much, and she immediately made changes. Now, she says, “I don't stack things one right after another. I give myself time to catch up to my body.”

In 2016, she started making her own performance pieces. This came about partly because of the open process of her mentors, Jane Comfort and Cynthia Oliver. About Comfort, she says, “She really cultivates your own creative practice. Even though it was very much her project and her choreography, I still had a voice in that room.”

Like her mentors, Leslie writes text for her own works. As a Black woman artist, she’s involved with identity issues but doesn’t want to be perceived only through that lens. “I grew up in a time where Alvin Ailey was my dream because that's all I knew as an option. I'm sort of masticating my need for expression of all of my stories without screaming from the rooftop about cultural or historical identity characteristics.”

On the practical side, Leslie has learned to be her own manager.

“It's a month-to-month, paycheck-to-paycheck kind of existence, and it's not easy,” she says. “You have to be businesslike and be clear about contracts, fees, and expectations.” Juggling all this has led her to the attitude that “performance is a form of self-care.”

Freelancing is not for everyone. But these three dance artists feel it’s all worth it. And New York is the city where the sheer abundance of dance commotion makes it possible. The bottom line, expressed by Emily: “I love the support, enthusiasm and empathetic intelligence that surrounds the New York City dance community.”

Where To See These Artists:

Deniz is touring with Mark Morris Dance Group in The Look of Love, appearing at Lehigh University October 17, 2025. He’s also joining the Trisha Brown Company on a 7-city tour as an understudy with the “Dancing with Bob” (Rauschenberg) evening. In the spring he’ll be dancing in the Metropolitan Opera’s production of Tristan und Isolde, with choreography by Annie-B Parson, and Eugene Onegin, with choreography by Kim Brandstrup. Follow @deniz.e.sancak on Instagram.

Emily will be performing at the Open Arts Studio Gala in Brooklyn on October 22, 2025. She is sharing a program in the Take Root series at Green Space in Queens on November 14, 2025.

Leslie is touring her own production, For All Your Life, making three stops: Krannert Center, Urbana-Champaign, IL October 17–18, 2025; Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston November 21-22; BAM Next Wave Festival, December 3–7, 2025. Follow @el_cuyjet on Instagram.

Created in 2020 as a way to lift up and include new voices in the conversation about dance, The Dance Enthusiast's Moving Visions Initiative welcomes artists and other enthusiasts to be guest editors and guide our coverage. Moving Visions Editors share their passion, expertise, and curiosity with us as we celebrate their accomplishments and viewpoints.